Style, University of Tennessee Journal of Architecture, No.

16, 1995, pp. 29-34

Revisiting Fascism:

Degenerate Art and the New Corporate Style

Michael Kaplan

Associate Professor of Architecture

University of Tennessee / Knoxville

"If only our totally superficial culture of today, which loves rapid

change, could visualize the future by learning to look more closely at the

past! This rage for innovation that collapses foundations, this foolish

negligence of the deep spiritual content in life and art, this modern concept

of life as a rapid sequence of instant pleasures, ... so many signs of decadence,

a sad denial of health and of the transcendent character of life." Martin

Heidegger(1)

The epigraph from Heidegger's Abraham a Sancta Clara, written in 1910

and excerpted by Victor Farias in Heidegger and Nazism, reveals a

virulent anti-modernist stance that later became the ideological substrate

of Nazi cultural revisionism. Appropriated by Hitler in his writings on the

degeneracy of modern art, this position formed the basis for the attack on

progressive German culture leading to a ban on art criticism in 1936 and

the slanderous Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibit of Germany's

great modern artists mounted in Munich in 1937.

The

relation of trends in the theoretical and practical architectural agenda

to the conservative political climate of the last two decades has become

a subject of speculation and debate. Bruno Zevi, advocate of modernism, argues

that certain formal aspects of historicism interface with ideological intents

of fascism.(2) Leon Krier, while acknowledging the appropriation

of the classical style by totalitarian forces, believes the convergence

incidental and not an indictment of the style.(3) David

Harvey, in The Condition of Post-Modernity, frames the debate in terms

of "a search for an appropriate myth" where modernist art served a capitalist

version of the Enlightenment, and classicism a reaction to the universalist

implications of technology.(4)

The

relation of trends in the theoretical and practical architectural agenda

to the conservative political climate of the last two decades has become

a subject of speculation and debate. Bruno Zevi, advocate of modernism, argues

that certain formal aspects of historicism interface with ideological intents

of fascism.(2) Leon Krier, while acknowledging the appropriation

of the classical style by totalitarian forces, believes the convergence

incidental and not an indictment of the style.(3) David

Harvey, in The Condition of Post-Modernity, frames the debate in terms

of "a search for an appropriate myth" where modernist art served a capitalist

version of the Enlightenment, and classicism a reaction to the universalist

implications of technology.(4)

In the context of the current debate, and within the framework of Harvey's

'appropriate myth' theory, this paper examines two examples of contemporary

architecture -- one historicist and the other modernist -- by relating their

stylistic language to the agenda of their patrons.

Whittle Headquarters: An Architecture of Decency and Deceit

The New Corporate Style -- as distinguished from the

curtain-walled office towers of the 1950s and 1960s -- is exemplified by

the corporate headquarters of Whittle Communications in Knoxville, Tennessee.

This company, now defunct, was partially owned by Time Warner Inc., and promoted

itself as being on the cutting edge of educational reform. The celebration

of pastiche in its headquarters, however, reveals a conservatism, indeed,

revisionism in its agenda.

The New Corporate Style -- as distinguished from the

curtain-walled office towers of the 1950s and 1960s -- is exemplified by

the corporate headquarters of Whittle Communications in Knoxville, Tennessee.

This company, now defunct, was partially owned by Time Warner Inc., and promoted

itself as being on the cutting edge of educational reform. The celebration

of pastiche in its headquarters, however, reveals a conservatism, indeed,

revisionism in its agenda.

Whittle had been active in three interrelated areas: the publication of magazines

directed at a specific clientele, the development of educational/commercial

television (including Channel One and the Whittle Educational Network), and

the development of a for-profit school system (The Edison Project). Whittle

publications developed a theme, were distributed free of charge, and contained

intensive advertising for products related to the theme. The Family Health

Adviser pamphlets, for example, were available, without cost, in the waiting

rooms of physicians' offices in a special display rack provided by Whittle.

The pamphlet itself contained about 40% advertisements related to the subject.

Channel One was conceptually similar. Television sets and satellite receiving

equipment were provided free of charge to the 9,000 schools (representing

about 6 million students) that enrolled in the plan. Schools were required,

by contract, to tune in daily to the 12-minute Whittle-produced news broadcast,

which contained 2 minutes of advertising. Channel One has been vigorously

opposed by many school systems as an invasion of a traditionally public,

non-commercial domain by private interests with their own commercial and

political agenda. This concern, among others, was raised in Kalamazoo, Michigan

recently when four teachers were reprimanded by their administrators for

refusing to air the news program during their classes. The Edison Project

is a further attempt to market mass education as a commodity by transferring

the design of education to the private sector. Whittle conceived and constructed

model schools would be supplied as part of a total education package to local

school boards. This concept shared similarities with the Education 2000

initiative of Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander who was, not surprisingly,

an early investor in Whittle Communications. Both Channel One and Edison

have the potential to reduce the prerogative of the teacher in disseminating

information.

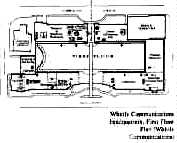

For Whittle corporate headquarters, designer Peter Marino

of New York created a 4-story complex described as an urban campus, occupying

two city blocks in downtown Knoxville. The site, formerly occupied by a Trailways

bus station and small retail/commercial venues, was bisected by Market Street,

a major pedestrian connection between the TVA complex at its northern end

and the City-County Building at the south. The city agreed to close a length

of Market Street, now incorporated within the gated Whittle complex, as the

north-south axis of a large, private open space. The new building did not

replace retail or commercial uses at the street level, and pedestrian activity

is limited to those who use its several entrances. It is an example of the

process of gentrification of downtowns, or what is left of them, that excludes

'dirty' uses.

For Whittle corporate headquarters, designer Peter Marino

of New York created a 4-story complex described as an urban campus, occupying

two city blocks in downtown Knoxville. The site, formerly occupied by a Trailways

bus station and small retail/commercial venues, was bisected by Market Street,

a major pedestrian connection between the TVA complex at its northern end

and the City-County Building at the south. The city agreed to close a length

of Market Street, now incorporated within the gated Whittle complex, as the

north-south axis of a large, private open space. The new building did not

replace retail or commercial uses at the street level, and pedestrian activity

is limited to those who use its several entrances. It is an example of the

process of gentrification of downtowns, or what is left of them, that excludes

'dirty' uses.

The neo-Georgian architecture, suggesting familiarity and

gentility, can best be described as 'decent,' one of several code-words used

by the Nazis to describe what 'degenerate' art was not. Philip Morris, editor

of Southern Living magazine, has called it "a darn good way to make

a building." Its brick facades pierced by small, double-hung windows suggest

traditional bearing-wall construction, but the building, responsive to a

1990 budget, has a steel frame with metal stud exterior walls clad in brick

veneer. The use of repetitive window openings might indicate partitioned

interior spaces such as small offices, but the space planning is efficiently

modern, with expansive open-plan work areas punctuated by enclosed rooms

that contain the more private functions. The insistent symmetry of the plan

contradicts the functionally-diverse physical program and a site that contains

many possibilities for asymmetrical development. Bruno Zevi assigns political

and psychological meaning to the use of symmetry:

The neo-Georgian architecture, suggesting familiarity and

gentility, can best be described as 'decent,' one of several code-words used

by the Nazis to describe what 'degenerate' art was not. Philip Morris, editor

of Southern Living magazine, has called it "a darn good way to make

a building." Its brick facades pierced by small, double-hung windows suggest

traditional bearing-wall construction, but the building, responsive to a

1990 budget, has a steel frame with metal stud exterior walls clad in brick

veneer. The use of repetitive window openings might indicate partitioned

interior spaces such as small offices, but the space planning is efficiently

modern, with expansive open-plan work areas punctuated by enclosed rooms

that contain the more private functions. The insistent symmetry of the plan

contradicts the functionally-diverse physical program and a site that contains

many possibilities for asymmetrical development. Bruno Zevi assigns political

and psychological meaning to the use of symmetry:

"Symmetry is the facade of sham power trying to appear invulnerable. [It

is] fear of flexibility, indetermination, relativity and growth -- in short,

fear of living."

"Symmetry is one of the invariables of classicism. Therefore asymmetry is

an invariable of the modern language. Once you get rid of the fetish of symmetry,

you will have taken a giant step on the road to a democratic

architecture."(5)

But democracy, or power through representation, is not what Whittle

was about. By hiding its true nature behind an historicist facade, the building

accurately reflects the philosophy of a company whose product is advertising

hidden behind a veneer of 'information.' (Whittle correctly and unapologetically

asserts that exposure to advertising is the price we usually pay to receive

information.) The project has, indeed, been considered by the architectural

press in terms of its image, rather than as a 'serious' piece of design.

Its visual language communicates a deliberate critique of modern architecture

-- indeed, of 'elitist' taste -- in a way that the populist language of the

company's publications delivers a subtle critique of intellectualism. Not

wishing to give it too much prominence or risk criticism for praising it,

Progressive Architecture chose a student intern writer to summarize

the building's (and the company's) message:

"In an age of star designers, it is refreshing to see work that clearly reflects

the will of a client, rather than the ego of the architect. Equally

refreshing is an office building which refuses to succumb to the 'corporate

aesthetic.' "(6)

The author fails to suggest that the Whittle headquarters represents a

new corporate aesthetic, one that is perhaps more efficient and audacious

than the old. The building, through its aesthetic, not only projects the

image of a company that confuses concern for society and concern for profit,

but subtly attacks those 'elitists' who might challenge its authority.

Degenerate Art: An architecture of respect and retreat

Designed by William Pereira in the 1960s and expanded by New York architects

Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates in the early 1980s, the Los Angeles County

Museum of Art is prominently situated on Wilshire Boulevard, competing as

an edifice and cultural institution with Arata Isozaki's Museum of Modern

Art downtown. The complex is described by Los Angeles historian Mike Davis

as a product of the desire of new (and mostly Jewish) money to legitimize

itself on its own turf.

"As if to precisely counterbalance the Music Center's pretensions to anchor

Culture securely in Downtown, LACMA, heavily endowed by the Ahmansons and

other Westside patrons, opened a few months later in the Jewish Hancock Park

area. Since the late 1940s the Westside had been staking claims for a distinctive

cultural identity beyond mere affinity with Hollywood."(7)

As part of its search for 'distinctive identity,' LACMA has in recent years

mounted shows of social conscience and controversy, the latest being

Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany. Curated

by Stephanie Barron, its gala opening in February, 1991, was attended by

none other than Madonna. The show contained 175 of the 650 objects originally

exhibited in Munich. The catalog, edited by the curator, attempts to draw

parallels between events in Nazi Germany and the latest manifestation of

artist-bashing in the United States, led by Senator Jesse Helms.

Robert Darnton, writing in the New Republic, criticizes the exhibit

as "strangely out of place in Los Angeles." I would disagree, arguing that

Los Angeles became the center of the emigre artist community in the United

States during and following the war, a haven for those who were rejected

by the Nazis, or those who feared for their careers and lives. Los Angeles

has been and continues to be a center of avant- garde art and architecture,

the LACMA building itself being the subject of ongoing critical controversy.

Finally, the exhibit was designed by local architect Frank Gehry, known for

his unconventional partis and dissonant juxtapositions of materials, an artist

who might well have been labeled "degenerate" by the Nazis.

Several critics of the exhibit have expressed discomfort,

if not disagreement, with the "parallel" theory, and Gehry expresses this

ambivalence of purpose by using an overly subtle display format. The designers

of the original Entartete Kunst chose to create a grotesque setting

to reinforce what they considered grotesque art. Paintings were hung,

intentionally tilted, against walls defaced by insulting rhetoric -- a device

obviously intended to titillate a curious public. By contrast, paintings

in the 1991 version were hung in an orderly. respectful way against white,

unadorned walls. Three-dimensional pieces were supported on substantial

Mission-style wood constructions reminiscent of the rough furniture constructed

by death camp inmates. Photographs of the original exhibit were mounted on

the walls to provide the historical context. What was missing was one of

the stated intents of the show: to graphically represent the parallel --

not the difference -- between then and now. This might have been accomplished

by the inclusion of works by contemporary artists considered obscene or

degenerate. With LACMA not having taken such a polemical stand, it is not

surprising, Darnton observes. that "the pictures look incapable of giving

offense."

Several critics of the exhibit have expressed discomfort,

if not disagreement, with the "parallel" theory, and Gehry expresses this

ambivalence of purpose by using an overly subtle display format. The designers

of the original Entartete Kunst chose to create a grotesque setting

to reinforce what they considered grotesque art. Paintings were hung,

intentionally tilted, against walls defaced by insulting rhetoric -- a device

obviously intended to titillate a curious public. By contrast, paintings

in the 1991 version were hung in an orderly. respectful way against white,

unadorned walls. Three-dimensional pieces were supported on substantial

Mission-style wood constructions reminiscent of the rough furniture constructed

by death camp inmates. Photographs of the original exhibit were mounted on

the walls to provide the historical context. What was missing was one of

the stated intents of the show: to graphically represent the parallel --

not the difference -- between then and now. This might have been accomplished

by the inclusion of works by contemporary artists considered obscene or

degenerate. With LACMA not having taken such a polemical stand, it is not

surprising, Darnton observes. that "the pictures look incapable of giving

offense."

Davis provides perhaps the most incisive explanation as to

why Gehry was chosen as architect of the exhibit:

Davis provides perhaps the most incisive explanation as to

why Gehry was chosen as architect of the exhibit:

"(Gehry's) portfolio is ... a mercenary celebration of bourgeois-decadent

minimalism. With sometimes chilling luminosity, his work clarifies the underlying

relations of repression, surveillance and exclusion that characterize the

fragmented, paranoid spatiality towards which LA seems to

aspire."(8)

Gehry's modernism, then, becomes a dialectic between relentless, cynical

critique of society. and service to his 'enlightened' capitalist patrons

as the "human face of the corporate architecture that is transforming Los

Angeles." His exhibit design for The Avant-Garde in Russia 1910-1930 (mounted

at LACMA in 1980) confirms his ability to respond boldly and sympathetically

to a given theme. Yet, in this sanitized design Gehry plays it safe, perhaps

not wanting to offend Holocaust sensibilities, perhaps not daring to challenge

the idea that 'it couldn't happen here.' By not taking a direct offensive

against contemporary critics of the arts, the exhibit has the effect of disarming

and pacifying its viewers. By its deflection of criticism and the blurring

of issues, its ends are remarkably similar to the Whittle project, though

its stylistic means are different.

Lessons of fascism

The ongoing controversy over governmental control of the content of artists'

work raises questions about the freedom professionals have to express their

concern on important and politically sensitive issues: the environment, the

state of the economy, civil rights, and the correctness of foreign policy.

When agents of political and economic authority (such as Whittle and LACMA)

become arbiters of taste, they have the power to not only physically shape

the environment in their image, but to manipulate thought as well. A submissive

cadre of artists whatever their stylistic language -- serves to legitimize

such power.

Modernism, in questioning and challenging the past, can serve as a vital

critic of the present. It can be a language of optimism and change, a sign

of life rather than decadence. The re-creation of Degenerate Art comes at

a time when modernism, however, is subject to assaults by politicians, designers

and entrepreneurs, and historicism vigorously promoted. In suggesting Seaside,

Florida as the New American Suburb, architect Andres Duany claims German

town planning during the Third Reich as one of his sources of inspiration.(9)

Seaside, with its authoritarian building code and derivative style, is, in

the end, a scheme for the affluent by an enterprising private developer,

hardly a paradigm for socially responsive urban development. Another of Duany's

patrons, HRH The Prince of Wales, chooses to ignore social issues by considering

contemporary design predominantly in 'archaicist' terms, favoring historicism

over history -- style over process. The wide acceptance of this kind of

reductionist thinking suggests that an alliance of patron/mentors, their

chosen developers and architects, and the establishment media can conspire

to set the standards for architectural and social critique, thus effectively

isolating and neutralizing those who might provide an alternative view.

Epilogue

Epilogue

Since this essay was conceived, there has been an array of remarkable events

related to its theses. HRH The Prince of Wales has established an architecture

school in London based on the principles set out in A Vision of Britain,

blurring the philosophical boundaries between populism and elitism, evoking

themes of the fascist past. The Whittle empire has collapsed financially,

its pieces sold individually to the highest bidders. In a eulogy written

in The New York Times, Whittle's former media relations director,

Gary Belis, stated that, "Even inside the company, you were always trying

to get a handle on what was real and what wasn't."(10)

Channel One was bought by K-III Communications Corporation, amid protests

by educators that it was a destructive influence in the schools. It continues

to function. The Edison Project remains under the guidance of Benno C. Schmidt,

Jr., although Chris Whittle has been removed as its chairman. The idea of

privatized schools awaits a political climate more sympathetic to its aim

of for-profit management of public education. Lamar Alexander, one of its

outspoken advocates, has announced his candidacy for President of the United

States, urging conservative activists to deal with "that little intellectual

elite" in Washington.(11) While referring specifically

to the current administration, he uses populist language that has broad and

chilling implications.

Of the pieces of the empire, the Whittle headquarters building has perhaps

come to the most ironic fate: it has been sold (at a supposed bargain-basement

price) to the federal government for remodeling into a new federal courthouse.

The same forces that favor the reduction of big government, the privatization

of public assets and the "free" operation of market forces, are quick to

advocate the transfer of private liabilities to the public domain through

legitimized salvage operations and direct subsidies.

While the building has changed hands, the values of power and capital that

created it remain very much alive, and move freely and conveniently between

private and public sectors as necessary or desired. The consolidation of

power that transcends private or public boundaries depends on the marginalization

of its critics for its success. Artists, traditionally among the avant-garde

of the criticized, are once again finding themselves in a compromised and

dangerous position. Shifts in the political spectrum have threatened the

reduction or elimination of federal funding of the arts. This will not end

art, but it will surely infringe on its autonomy and thereby serve to hush

some of society's most persistent, strident and needed critics.

-----

Michael Kaplan is Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of

Tennessee in Knoxville. He lectures and writes on social, political and cultural

aspects of design. This essay is adapted from a presentation given at

FASCISM[S]: Roots/Extensions/Replays, an interdisciplinary graduate

student conference held at The University of Oregon in April 1992. E-mail:

mkaplan@utkux.utcc.utk.edu.

________________________

1 Victor Parias, Heidegger and Nazism (Temple University

Press, Philadelphia 1989), p. 32

2 Bruno Zevi. The Modern Language of Architecture

(University of Washington Press, Seattle 1978), pp. 15-22

3 Leon Krier, "An Architecture of Desire," Architectural

Design, April 1986

4 David Harvey, The Condition of Post-Modernity (Basil

Blackwell, Cambridge 1989). pp. 34-35

5 Bruno Zevi, p. 15

6 Stephen Case. "Campuslike HQ for Whittle in Knoxville,"

Progressive Architecture, October 1991, pp. 18-19

7 Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in

Los Angeles (Verso, New York 1990). p.72

8 Mike Davis, pp. 236-238

9 Duany's comments were included in his presentation at the

1985 AIA convention in Lexington, Kentucky.

10 Elliott, Stuart, "Whittle Communications' Fall Is Dissected"

The New York Times, October 24, 1994

11 Alexander urges ousting 'intellectual elite'," The Knoxville

News-Sentinel, February 10,1995, p. A9

_________________________________________________________

[Graphics captions]

Hitler's sketch for the Great Hall planned for Berlin, 1925

Whittle Communications' Family Health Advisor, showing theme-related advertising

Whittle Communications headquarters for Knoxville, 1991

Whittle Communications headquarters, First Floor Plan

Interior of a barrack a Birkenau camp, Poland

Degenerate Art exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Chris Whittle and Lamar Alexander

Copyright 1995, Michael Kaplan and University of Tennessee School of Architecture

[End]

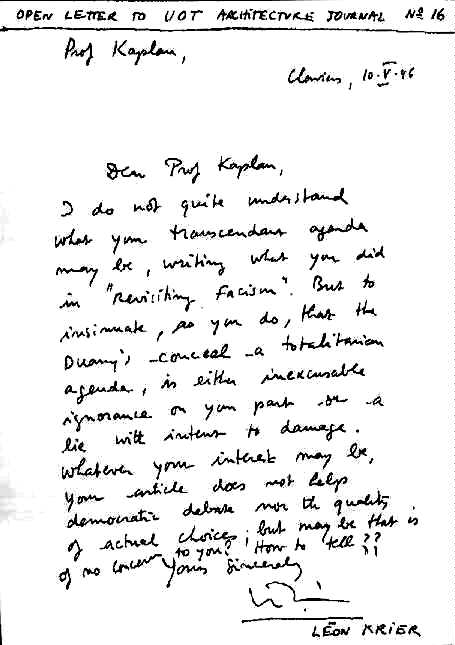

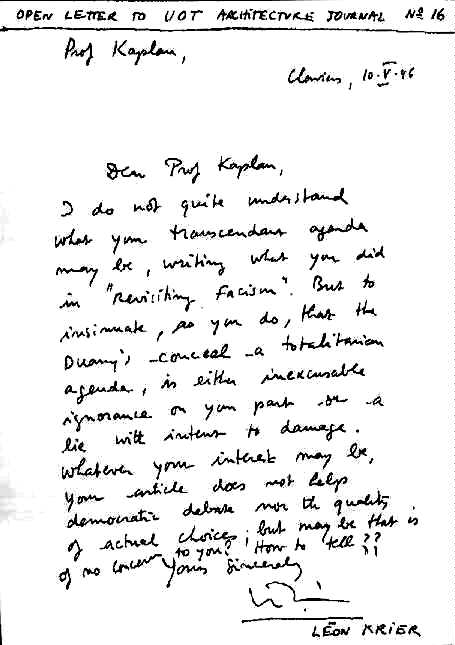

[Fax from Leon Krier to Professor Kaplan]

Fax emis par: 94478594 KRIER-CLAVIERS

OPEN LETTER TO UOT ARCHITECTURE JOURNAL No. 16

Prof Kaplan, Claviers, 10.V.96

Dear Prof Kaplan,

I do not quite understand what your transcendant (sic) agenda may be, writing

what you did in "Revisiting Fascism." But to insinuate, as you do, that the

Duany's -conceal- a totalitarian agenda, is either inexcusable ignorance

on your part -or- a lie with intent to damage. Whatever your interests may

be, your article does not help democratic debate nor the quality of actual

choices; but may be that is of no concern to you? How to tell??

Yours sincerely,

[Signature]

Leon Krier

[End]

[Krier's fax original]:

The

relation of trends in the theoretical and practical architectural agenda

to the conservative political climate of the last two decades has become

a subject of speculation and debate. Bruno Zevi, advocate of modernism, argues

that certain formal aspects of historicism interface with ideological intents

of fascism.(2) Leon Krier, while acknowledging the appropriation

of the classical style by totalitarian forces, believes the convergence

incidental and not an indictment of the style.(3) David

Harvey, in The Condition of Post-Modernity, frames the debate in terms

of "a search for an appropriate myth" where modernist art served a capitalist

version of the Enlightenment, and classicism a reaction to the universalist

implications of technology.(4)

The

relation of trends in the theoretical and practical architectural agenda

to the conservative political climate of the last two decades has become

a subject of speculation and debate. Bruno Zevi, advocate of modernism, argues

that certain formal aspects of historicism interface with ideological intents

of fascism.(2) Leon Krier, while acknowledging the appropriation

of the classical style by totalitarian forces, believes the convergence

incidental and not an indictment of the style.(3) David

Harvey, in The Condition of Post-Modernity, frames the debate in terms

of "a search for an appropriate myth" where modernist art served a capitalist

version of the Enlightenment, and classicism a reaction to the universalist

implications of technology.(4)

The New Corporate Style -- as distinguished from the

curtain-walled office towers of the 1950s and 1960s -- is exemplified by

the corporate headquarters of Whittle Communications in Knoxville, Tennessee.

This company, now defunct, was partially owned by Time Warner Inc., and promoted

itself as being on the cutting edge of educational reform. The celebration

of pastiche in its headquarters, however, reveals a conservatism, indeed,

revisionism in its agenda.

The New Corporate Style -- as distinguished from the

curtain-walled office towers of the 1950s and 1960s -- is exemplified by

the corporate headquarters of Whittle Communications in Knoxville, Tennessee.

This company, now defunct, was partially owned by Time Warner Inc., and promoted

itself as being on the cutting edge of educational reform. The celebration

of pastiche in its headquarters, however, reveals a conservatism, indeed,

revisionism in its agenda.

For Whittle corporate headquarters, designer Peter Marino

of New York created a 4-story complex described as an urban campus, occupying

two city blocks in downtown Knoxville. The site, formerly occupied by a Trailways

bus station and small retail/commercial venues, was bisected by Market Street,

a major pedestrian connection between the TVA complex at its northern end

and the City-County Building at the south. The city agreed to close a length

of Market Street, now incorporated within the gated Whittle complex, as the

north-south axis of a large, private open space. The new building did not

replace retail or commercial uses at the street level, and pedestrian activity

is limited to those who use its several entrances. It is an example of the

process of gentrification of downtowns, or what is left of them, that excludes

'dirty' uses.

For Whittle corporate headquarters, designer Peter Marino

of New York created a 4-story complex described as an urban campus, occupying

two city blocks in downtown Knoxville. The site, formerly occupied by a Trailways

bus station and small retail/commercial venues, was bisected by Market Street,

a major pedestrian connection between the TVA complex at its northern end

and the City-County Building at the south. The city agreed to close a length

of Market Street, now incorporated within the gated Whittle complex, as the

north-south axis of a large, private open space. The new building did not

replace retail or commercial uses at the street level, and pedestrian activity

is limited to those who use its several entrances. It is an example of the

process of gentrification of downtowns, or what is left of them, that excludes

'dirty' uses.

The neo-Georgian architecture, suggesting familiarity and

gentility, can best be described as 'decent,' one of several code-words used

by the Nazis to describe what 'degenerate' art was not. Philip Morris, editor

of Southern Living magazine, has called it "a darn good way to make

a building." Its brick facades pierced by small, double-hung windows suggest

traditional bearing-wall construction, but the building, responsive to a

1990 budget, has a steel frame with metal stud exterior walls clad in brick

veneer. The use of repetitive window openings might indicate partitioned

interior spaces such as small offices, but the space planning is efficiently

modern, with expansive open-plan work areas punctuated by enclosed rooms

that contain the more private functions. The insistent symmetry of the plan

contradicts the functionally-diverse physical program and a site that contains

many possibilities for asymmetrical development. Bruno Zevi assigns political

and psychological meaning to the use of symmetry:

The neo-Georgian architecture, suggesting familiarity and

gentility, can best be described as 'decent,' one of several code-words used

by the Nazis to describe what 'degenerate' art was not. Philip Morris, editor

of Southern Living magazine, has called it "a darn good way to make

a building." Its brick facades pierced by small, double-hung windows suggest

traditional bearing-wall construction, but the building, responsive to a

1990 budget, has a steel frame with metal stud exterior walls clad in brick

veneer. The use of repetitive window openings might indicate partitioned

interior spaces such as small offices, but the space planning is efficiently

modern, with expansive open-plan work areas punctuated by enclosed rooms

that contain the more private functions. The insistent symmetry of the plan

contradicts the functionally-diverse physical program and a site that contains

many possibilities for asymmetrical development. Bruno Zevi assigns political

and psychological meaning to the use of symmetry:

Several critics of the exhibit have expressed discomfort,

if not disagreement, with the "parallel" theory, and Gehry expresses this

ambivalence of purpose by using an overly subtle display format. The designers

of the original Entartete Kunst chose to create a grotesque setting

to reinforce what they considered grotesque art. Paintings were hung,

intentionally tilted, against walls defaced by insulting rhetoric -- a device

obviously intended to titillate a curious public. By contrast, paintings

in the 1991 version were hung in an orderly. respectful way against white,

unadorned walls. Three-dimensional pieces were supported on substantial

Mission-style wood constructions reminiscent of the rough furniture constructed

by death camp inmates. Photographs of the original exhibit were mounted on

the walls to provide the historical context. What was missing was one of

the stated intents of the show: to graphically represent the parallel --

not the difference -- between then and now. This might have been accomplished

by the inclusion of works by contemporary artists considered obscene or

degenerate. With LACMA not having taken such a polemical stand, it is not

surprising, Darnton observes. that "the pictures look incapable of giving

offense."

Several critics of the exhibit have expressed discomfort,

if not disagreement, with the "parallel" theory, and Gehry expresses this

ambivalence of purpose by using an overly subtle display format. The designers

of the original Entartete Kunst chose to create a grotesque setting

to reinforce what they considered grotesque art. Paintings were hung,

intentionally tilted, against walls defaced by insulting rhetoric -- a device

obviously intended to titillate a curious public. By contrast, paintings

in the 1991 version were hung in an orderly. respectful way against white,

unadorned walls. Three-dimensional pieces were supported on substantial

Mission-style wood constructions reminiscent of the rough furniture constructed

by death camp inmates. Photographs of the original exhibit were mounted on

the walls to provide the historical context. What was missing was one of

the stated intents of the show: to graphically represent the parallel --

not the difference -- between then and now. This might have been accomplished

by the inclusion of works by contemporary artists considered obscene or

degenerate. With LACMA not having taken such a polemical stand, it is not

surprising, Darnton observes. that "the pictures look incapable of giving

offense."

Davis provides perhaps the most incisive explanation as to

why Gehry was chosen as architect of the exhibit:

Davis provides perhaps the most incisive explanation as to

why Gehry was chosen as architect of the exhibit:

Epilogue

Epilogue